Last July, I had the opportunity to attend the Historical Thinking Summer Institute (HTSI) in Ottawa. HTSI is a one-week conference held each summer for people involved in historical research and education. Our week was split between the National History Museum and the Canadian War Museum, and some of the perks included exploring the physical archives ‘behind the scenes’ at the museums, and hearing directly from museum curators on how they select material for their exhibits.

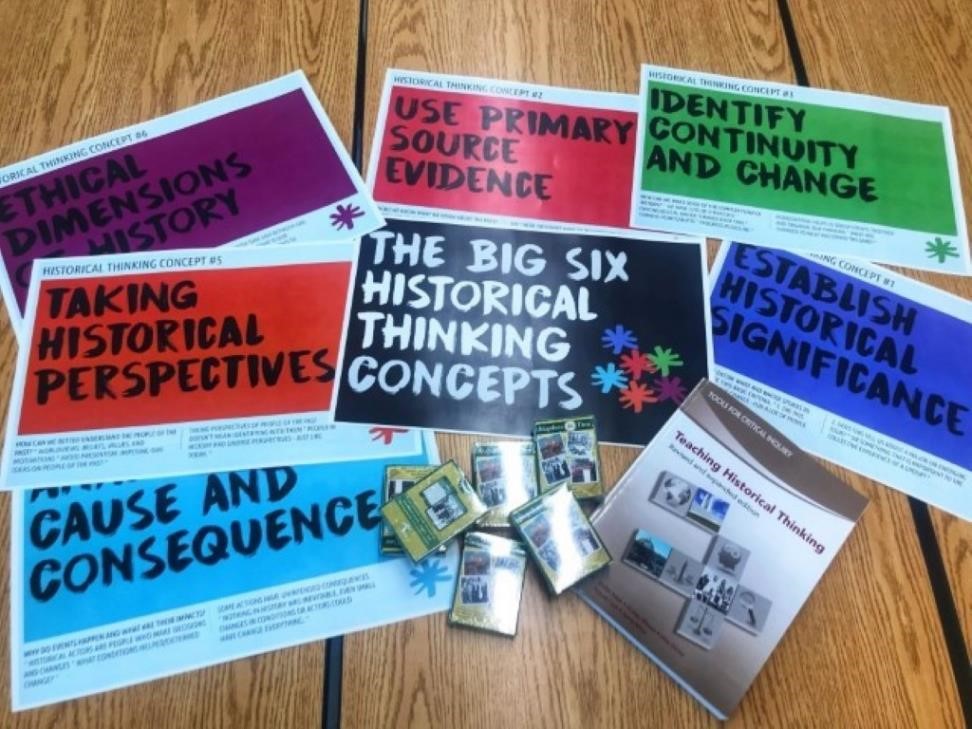

Historical thinking, for the uninitiated, revolves around six concepts we use to study the past. We spent a half-day working with each of them at HTSI:

- Establish historical significance

- Use primary source evidence

- Identify continuity and change

- Analyze cause and consequence

- Take historical perspectives, and

- Understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.

I was already familiar with the concepts before this summer; they are the cornerstone of the Grade 11 History of Canada curriculum. Even so, I was surprised how much I learned and how much my understanding was challenged in one week at HTSI.

To begin with, I expected an audience of mostly high school teachers. But in reality, high school history teachers represented a small fraction of the attendees. Many of the people I worked with during the institute were archivists, museum staff, professors, grad students, and early-years teachers. Most were Canadian, but there was also a group of teachers from Israel and one attendee from Belgium.

The diverse perspectives strengthened my experience. People from outside of K-12 have entirely different challenges in teaching history than we do in schools. For example, the museum people discussed the pressure to give a complete story of an event while keeping up the entertainment value to attract visitors. In some ways, this is similar to the demand for teachers to keep lessons meaningful and engaging. Unlike us, a lot of their administrators encourage them to have learners read less. When we explored using historical perspectives and ethical uses of history to get a better sense of an event, the group from Israel opened up about how difficult that can be, given political tensions in their communities.

One group I learned the most from were the early-years teachers. A couple of big push backs against historical thinking among many high school teachers is that it takes time, and not all of our students are mature enough to handle the six concepts on top of learning content. The early-years teachers I met squashed those perceptions: I sat with a first-grade teacher from PEI who told me how she uses each of the concepts with her students. Time certainly isn’t plentiful in her classroom, and if high school teachers complain about a lack of background knowledge in teens, six-year-olds have even less.

The other significant surprise for me was how much the professors leading the institute emphasized the importance of content knowledge. One of the criticisms of historical thinking I’ve heard often among colleagues (and I have been part of this group) is similar to some of the questions raised regarding Deeper Learning in general: are we sacrificing content for skills? With each concept, our instructors stressed that students need a rich content understanding of historical events to utilize historical thinking. The emphasis on content knowledge makes sense: my students can’t discuss the ethics involved in how we present the story of Louis Riel unless they know what his story is in the first place.

What now? I’ve nearly completed one semester teaching after attending HTSI. Like many of us working with Deeper Learning, most of what I do in my classroom is regularly under construction. I have lessons related to historical thinking skills that my students have LOVED. I have others that need re-working. I’ve noticed that my adapted students tend to lend themselves more naturally to historical thinking compared to my students with grades in the 90s. I think the biggest reason is they are less grade-obsessed: my adapted kids are more open to inquiry and investigation, and the ambiguity initially involved in those tasks because they aren’t as afraid to make a mistake. So, some of my next steps are pedagogical – but a lot of them involve addressing students’ mindsets as well.

If you are interested in diving deeper with historical thinking, these are a couple of the resources I have found helpful:

- The Historical Thinking website has a ton of linked resources and lessons.

- Teaching Historical Thinking (2017) by Miles, Gibson, et al. A book co-written by one of the leaders of HTSI had a TON of practical applications, including BLMs, for using historical thinking in K-12.

Want to Attend? Also worth noting, for anyone interested, is that the Historical Thinking Summer Institute is being held in Winnipeg this summer, and there is funding available through our Social Sciences SAGE group for those interested. You can find out more on their website. I can’t encourage this PD opportunity enough: it was some of the best professional development I’ve attended in several years.

SRSS Author: Jolene Fiarchuk